Nottinghill Forest Garden – 2012: Consolidation & Diversification – Part B

This is Part Three (B) of a series of Articles, that critically discuss’s the Nottinghill Forest Garden Project from Analysis – to Implementation – to Future Idea’s.

Part One can be found here.

Part Two can be found here.

Part Three (A) can be found here.

2012: Consolidation & Diversification

Spring Cover Cropping

March: Late spring

Water harvesting feature upgrades, complete by the first week of March, were installed just in time for an explosion in plant growth and general garden activity. By March 14th, total temperature variation during the day was well above normal: the lows were higher than the average high temperature. We experienced over ten days where the low temperature remained around 60F (15.5C). Growing temperature is considered to be 50F or 10C, so we were well into spring. Remember that the “last frost date” for our region is May 1st. A month and a half beforehand, the garden burst into life.

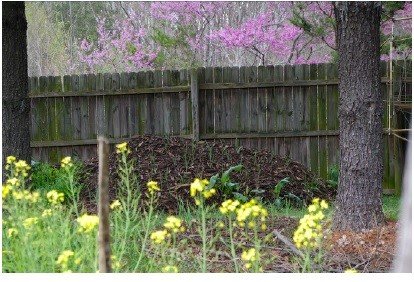

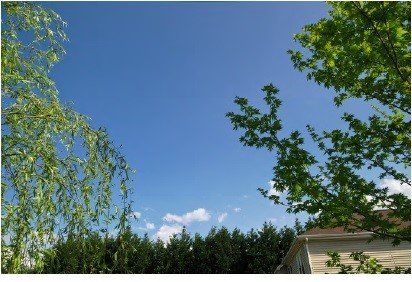

Photograph 3-27 displays quite well the strong growth our cover crops experienced through the winter, as well as the tendency of willows to break dormancy well before the natives (all the other tree branches are from native species). A couple of days later, I captured a photograph of the first bumblebee to make the rounds in the garden. Bumblebees work harder and pollinate more effectively than the introduced honey bee. They also forage at much colder temperatures. This particular worker bee is gathering nutrition from a cabbage plant.

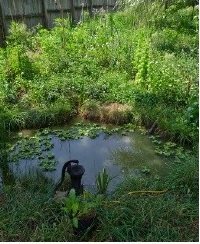

The bees weren’t the only ones enjoying the warming weather. The goldfish I introduced to the upper pond for mosquito control the year prior were spawning as well. In Photograph3-28, water hyacinth can also be observed breaking dormancy.

As we enter the end of the first week of the warm spell, the garden- fresh off months of good rainfall and water harvesting- began to grow much quicker. All of our brassicas (cabbage family) have entered full floral displays and the cover crops are soaking up all the solar energy that a clear canopy allows to reach ground level. This is a crucial period in a garden: these herbaceous plants that can tolerate cold weather are holding onto and putting to use any waterborne nutrient. When they are cut back and allowed to decompose/return to the soil over the coming months, these nutrients will become available to the trees and other plants which wait longer to break dormancy. I would like to find more native (and nonnative) early bloomers to enhance this “vernal dam.”

You can also see how clearly the native trees are resisting the warm spell’s charm. They have genetic knowledge that these warm periods can quickly end, and therefore, bide their time.

One of our Russian comfrey plants on the berm of the second swale, right where water pools in the center of the swale’s length, was at full cutting size by the end of March- over a month before the last frost date. The key to utilizing comfrey for biomass production is to cut the plant before it begins making flowers for the first time. It is at this stage that you will get the most leaves and the plant will be conditioned to keep producing lots of leaves rather than flower stalks. Although the comfrey had proved itself extremely hardy (it never rested from putting out new leaves all winter), I wanted to make sure that they were as healthy as possible in the face of a sudden cold snap. I did not take advantage of this very crucial moment in time, however, I am happy to have captured the moment in a photograph.

2012

Three days later, the eastern redbuds (Cercis Canadensis) planted alongside the interstate were blooming. Contrary to popular belief, they have not been observed to fix nitrogen although they belong to the legume family (Fabaceae). A cardinal, the state bird of North Carolina, can also be observed in the branches in the background (left, red). The foreground is dominated by flowers from the brassicas we planted the previous fall. Center of attention, framed by pines, are our mini hugel beds that I mulched with wood chip from the city. Planted there were dozens of garlic cloves. They grew to a very small size due to a number of factors. One of those being not enough sun: the angle of the sun does not drop low enough for these beds to get proper solar exposure during the winter. If the trees were limbed up another meter, I believe they would. However, we would lose a line of sight visual break that shields part of the highway from view. I was still happy that they survived because they could be dug up and transplanted to other locations in the garden (as well as being eaten!).

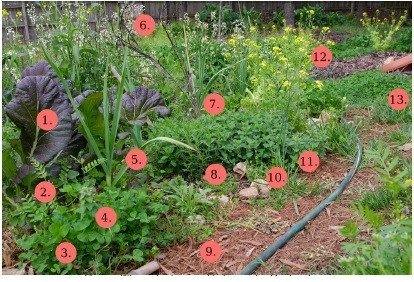

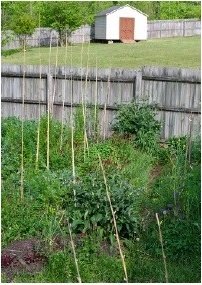

The last photograph from March, which I have annotated to become Figure 3-2, captures the moment of transition from winter cover crop to early spring in the garden. Fall sown winter crops are in their final stage of development: they’ve grown into an over story of flowering stems while perennial herbs break dormancy and other cover crops, such as common vetch and red clover just begin flowering. Stacking space and time for the longest period of blooms possible is an important part of our plan to regenerate our landscape. Nothing says that leaf crops cannot be used in this process!

April: Summer arrives a month early

Looking back on the meteorological record for April, we couldn’t have been more lucky. The unseasonably warm weather in March fostered extremely strong early spring growth- which is exactly what we needed to help meet our goal of producing as much biomass as possible before the trees close the canopy. Unseasonably warm weather can be a double edged sword: if that trend had continued through April, much of those gains could have been compromised. If temperatures climb too high, humid conditions could easily begin to create mildew problems and otherwise stress the plants. So we were lucky that temperatures fell back into the “normal” range between 50 and 65 F (10-18C).

While I held off on planting summer species in March, by April I was ready to make the bet and we planted sunflowers and peas along the temporary fence. With the motto of “let the plants fend for themselves,” we simply made small hills of compost and mulch all along the dog fence. The peas would have little trouble climbing the fence and sunflowers are rather hardy. However, we since we didn’t do anything to amend the soil here, there was a risk that they would not grow very well with only a little compost on top of compacted soil.

A few days later, I observed some of our first mushrooms emerging from the soil. I should make friends with some mycologists so I can ask them to help identify these amazing creatures. At any rate, it shows that the wood chip mulch was starting to be broken down exactly as predicted. It is a humbling experience to sit underneath a tree and contemplate the living, breathing mycelial networks that are busy colonizing a garden. It is relieving to know that they are working out the most efficient pathways to nutrients, holding onto the soil, organic materials, and water while promoting their microbial allies underground- all beyond the naked eye.

The only sizable addition to the garden was sheet mulched during the first week of April. Before sheet mulching, we slightly decompacted the soil through the use of a garden fork (in the same action as a broad fork, but less efficient) and spread a thin layer of dolomitic lime along with a dusting of organic fertilizer. Then, dampened cardboard was overlaid thickly. We did not add any compost to this layer in order to save money. The intent here was to transplant some native plants we had stratified during the winter and otherwise colonize this area of the property with cover crops. Some vegetables would be sown as well for added diversity.

It wasn’t until the end of the first week that the red maple leafed out. About the same time, other natives, such as poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) were also emerging from their winter slumber. Poison ivy can be considered the Achilles Heel of forest gardening in eastern North America. If left unchecked, poison ivy will quickly take advantage of better growing conditions and can prevent human activity. Since the entire plant produces a highly allergic oil, it is extremely difficult to get rid of. Strong root systems- including air roots on older vines- allow it to quickly regenerate after being set back. It is perhaps the only plant we consider the use of herbicides to help in our overall control scheme. Prevention- by filling the niches- and early eradication while the plants are still young are the long term realities of sharing the same ecosystem with this plant.

Even in the newly sheet mulched bed, we needed to create pathways. Keyhole design came in handy here. Short, terminal pathways running perpendicular to the slope do not create much potential for erosion in this situation because the catchment of this berm is so small. These paths were mulched deeper than the rest of the bed so that our compaction underneath them would be minimized.

Shortly after, crimson clover (one of three clover species in the garden) began to bloom. Crimson clover is hardy, self-seeding annual. We have sown it on the swale berms between the comfreys to ensure that the comfrey has enough nitrogen to support its incredible metabolism. It will self-sow and return to growth in the fall. We will still collect some seeds for future use in other areas though! About the same time, the older comfrey plants were in full bloom as well. The entire garden was resplendent with generalist nectary species. What was still missing, however, were enough specialist nectary plants to really support the populations of predatory insects.

With a full herbaceous layer, the soil has a better chance of being protected as spring turns to summer. Strong, healthy plants covering the soil allow the soil to come to life as the rood exudates and mycorrhiza associations accelerate. Without plants, the primary producers in the ecosystem, the soil will not improve. Additionally, this community of plants is better able to protect the soil from the elements: wind, UV radiation, and precipitation. Soil organisms are able to work the entire soil profile since the surface stays cool and moist. We have multiple functions all without needing to pick up anything other than the camera at this point.

It always helps to observe other landscape practices in addition to our own. Our neighbor’s lawn to the east just so happens to be the one directly observable from our garden. Contrast the dull, almost brown and dry looking lawn to the area around our first/upper swale. While we still have the shrub layer to fill (the tree layer is taken to the north by the red maple), we have a very strong start to a diverse and resilient system. Comfrey acting as a cornerstone species of the function we wish to derive from the swale: water and nutrient harvesting. Comfrey is supported by crimson clover for nitrogen fixation, and lemon balm plus garlic for aromatic pest confusion. Additionally cilantro (or coriander for the rest of the English speaking world), is providing abundant specialist nectary solutions for the polyculture. Into all of this, other species such as oregano, lettuce, mustards, Echinacea only add more complexity and uses to this multi-functional system. This one small patch of garden probably has more life in it than the entire lawn!

The existing trees in the forest garden are receiving a tremendous influx of nutrients and soil building capacity. The willow, pictured below, has crimson clover, red clover, white clover, and alfalfa all fixing nitrogen within its root zone. It sits just above the low spot of the second/lower swale and so is periodically flooded when large rain events occur. This is a niche that willows thrive in. With comfrey also planted under its drip line, the willow will have access to a slow release of minerals mined from deep in the soil. Other herbs and plant species also find their home amongst this sea of green.

Stepping back a bit, this next photograph captures the changing light conditions brought about by summer solar angles and a canopy in leaf. When the western most trees- the willow oak and twin river birches- have closed their crowns, the northern half of the garden is in deep shade by midafternoon. This is desirable in an environment with high summer evaporation rates. The trees will shade our water harvesting and storage features, creating a cool retreat. Because solar energy at this latitude is so intense, even 4 hours of direct summer sun is enough to produce garden vegetables. Dappled shade during the course of the day and a deep shadow during the peak of the afternoon creates a wonderful microclimate. The area around the willow and maple, (center, background) is fully exposed to the sun and care needs to be exerted not to allow the sun to desiccate the soil.

Going to the other boundary of the garden and looking north (and downslope), we can see yet again how patches of the garden develop differently in relation to the amount of sunlight. The foreground is the old green guild, where I had planted plenty of white clover along the pathways. Being rhizomatous, the clover has spread to form very thick ground cover. Perennial herbs and strong winter crops like brassicas are able to hold their own ground and compliment the clover nicely. Still, things are a bit slower here. The comfrey, while flowering, is perhaps only half as thick as comfrey grown on the swale berms with access to full sun. The slower growth is a boon because we can extend the season on cool weather crops.

Before the mulch sale season came to a close, we invested in a few more cubic yards of wood chip. Here, you can see how we have heavily mulched underneath the ornamental plum to about its drip line. Because the soil in this area had been scalped by the lawn mower, it was in dire need of some repair work. Underneath the twin river birches (framing the wheelbarrow), an extra thick layer- about 8” (20cm) of wood chip was laid down. These areas are highly trafficked and without supplemental wood chip, the soil would once again be exposed to the elements. Very thick mulch will allow the tree roots and fungal associates to slow, spread, and sink water. We also laid a strip of wood chip directly adjacent to the temporary dog fence in order to provide a place where we could sow some flowers to help break up the harsh transition from lawn to garden. The one very clear patch of clay that is shaped like a shallow U is the remains of a water retaining feature that was to be included in the garden, but never completed after the fence was moved.

The last photographs from April depict the areas around the first and second swales. Both are thriving plant communities helping us meet our goals for 2012: consolidation and diversification!

Summer Soil Building

May: Chop and Drop Begins

May is the first month during which temperatures should only in a very rare event drop to freezing. By the first of May in 2012, the threat of frost was so marginal that I almost felt ridiculous to have waited so long before engaging in the chop and drop regime we had planned. Part of this is because, as I mentioned earlier with comfrey, many plants we want to use in a chop and drop regime, like alfalfa and red clover, have their greatest biomass ready just before flowering. Once they begin to flower, they start to get leggy, like many vegetables do when they bolt. Cut for mulch at this point, they will have less biomass available. Still useful, just a little less to work with. And as with comfrey, some plants, once they have already flowered once, will regrow with reproduction in mind rather than staying in a strictly vegetative state. Of course, another potential downside to waiting so long is that even if the flowers are not quite yet ready to set seed, it is possible that there will be enough strength left in the stems to ripen seed after cutting. So you risk spreading seed from plants you cut. This isn’t really a problem in our situation, since we would be happy to spread red clover and alfalfa around our garden at this point in time. However, if you apply the “chop and drop” regime to undesirable species, attention should be paid to whether they have flowered or not.

You may be asking, what is “chop and drop”?

The technique refers to the literal “chopping” of a plant (or parts of it) and dropping the organic material onto the ground. Plants maintain a certain root to shoot ratio, so when you cut back portions above ground, the plant will shed some roots. This is called “rhizodeposition.” Why this matters is that, as plants are the primary engines of the soil food web, intentionally forcing plants to shed roots means that more carbon can be pumped into the soil than if the plants were left to go through their life cycle without any interruption.

Since the red clover and alfalfa was planted all the way back in the fall of 2011, the plants had all winter and the warm spring to grow deep root systems. By waiting until plants are established, we can rest assured that they have the root infrastructure necessary to withstand this kind of shock treatment. Also paying attention to the weather- will there be enough rainfall for the plants to regrow with vigorous necessary if you want to maintain this regime. Chop and drop should not be a chore done every other week without regard for how the system is evolving.

The material chopped is oftentimes just “dropped” onto the soil. In small systems, where attention to detail is possible, carefully placing the cut material around the crown of the plants you just cut is important to allow the crown to get air. This will help prevent crown rot. Cut material can also be transported throughout the garden to locations you think would benefit from some extra mulch, such as recently transplanted vegetables or trees. Care should also be taken to avoid cutting too late in the season. Allowing the plants to gather as many resources as possible late in the summer/ early autumn means they will have enough stores to withstand the coming winter.

One other reason I waited so long to initiate the rhythm of chop and drop was that I wanted many of them to flower to provide nectar. If I waited long enough, the entire garden would be in bloom. If I began to cut back plants at towards the top of the garden, there would still be flower-based food available throughout the rest of the garden.

To help compensate for the amount of stress that these plants will be under, I began to brew aerated compost tea. Any permeable material that will not allow large particles to leave will work very well for holding vermicompost and other high humic acid materials as an air pump/stone keeps the concoction oxygenated. After about 24 hours, a thick froth appears on the surface and the tea has a strong, earthy smell. It is then ready to be diluted and either sprayed or used as a soil drench. It is best to use right away as the number of organisms begins to decline rapidly once aeration is ceased and the organisms have used up many of the nutrients present. These compost teas were then used to boost plants stressed by being cut. Whether the influx of millions of organisms actually helps out compete with disease causing organisms or if the plant available nutrition from the tea is what helps prevent the “patient” from falling ill is hard to say with absolute certainty, but it is probably a combination of the two.

The decision to dig ponds is a major attractor for birds of all kinds. With fresh water available throughout the year, birds will begin to keep our garden on their migratory flight path. Year round residents already know our garden and visit often. Before the garden has a proper shrub layer, birds can be encouraged to scout for food by allowing the dead stalks of annuals to stand throughout the year. Bamboo stakes, fallen limbs with branches, bird feeders (without any food even!), and anything else remotely resembling a perch will be put to use in no time. I have found that adding stakes to the ground is a great way to improve spider habitat before any plants are tall enough to meet their needs. If untreated wood, especially branches, are used in this manner, they will also act as soil stakes which will eventually be colonized by fungi and break down as a high carbon input.

In the first few days of May, I sowed the newly sheet mulched bed with a diverse range of cover crop seeds and vegetables, including okra that we harvested from the year prior. These were simply broadcast by hand Sepp Holzer style in an effort to minimize work and meet the maintenance goal of letting the plants do the work for themselves. If the seeds survived, great, if not, then they weren’t meant to be there at the time. We also had perennial natives and some other vegetables started that would be transplanted later.

Before heading out for a long weekend, I cut a large amount of white clover from the former green guild to mulch the seeds. The mulch would prove to “wet” and the seeds were too quick to sprout, so many were smothered by my good intentions!

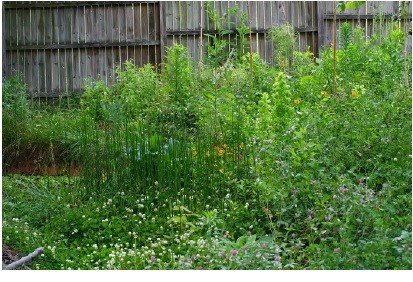

Photograph 3-61 captures the moment when the garden was absolutely covered in blooms, and thus, ready to begin chop and drop. Growth was so thick that our secondary paths were entirely engulfed by red clover and alfalfa. Cutting them back will improve the flow of air throughout the garden.

Using nitrogen fixing plants as the major species for chop and drop soil building regimes means that some of the nitrogen in the root nodules will become available to the soil food web, potentially fertilizing neighboring plants like the lettuce, garlic, and cilantro photographed here. Before their stems and leaves are consumed by the soil, they will act as a bulky mulch to protect the ground in the same way they did as in life. With a little bit of breathing room and more nutrients available, the vegetables will be able to grow a little quicker and be ready to harvest shortly.

With the brassica seeds ripening, birch catkins on the wane, and insects in demand for baby birds, our garden became a hotbed of activity. Simply being still for about 10-15 minutes was enough to have multiple species drop by for a visit. Photograph 3-63 captured four species in one shot. A cardinal swoops in top center left, a house finch perches on a mustard plant devouring seed, an unidentifiable sparrow perches atop a bamboo stake that was holding the mustards upright, and a goldfinch is sitting on a birch branch (top center). The diversity of food available through the deliberate encouragement of niche diversification opens the garden to many interactions. I am happy to allow bird populations to feed on seed from our crops because they cannot eat literally every seed (leaving the missed ones to join the seed bank) and their presence means that insects are devoured and guano left for fertilizer. Of course, they also can bring in seed from elsewhere, but we focus on the positive. Additionally its just a lot of fun to watch so many different birds enjoying themselves!

To truly appreciate how intense the herbaceous layer grew by early summer, one needed to step back onto the berm and take it all in from under the pines. What looks to the uninitiated observer as a field of weeds, is to a permaculturalist a sign of rapid carbon capture and nutrient gathering. The garden even shocked another permaculture enthusiast with in its “feral” condition! I thought it was an absolutely incredible experience to behold plants not just being allowed to express their potential, but actively encouraged. I can see how this kind of gardening may be intimidating, but once you get out and walk the pathways and peek closer, it should be very clear that everything has a purpose.

All of the cabbage, mustard, arugula, radish, and other winter greens have long since finished flowering and have had their generalist nectary niche replaced with white clover, red clover, and alfalfa in the main with comfrey backing them up. Yarrow, cilantro and parsley were, at the time, our only obvious specialist insectary species as the sunflowers and New England asters would bloom later in the summer.

The red clover and alfalfa (to a lesser extent) grew so densely that other species living amongst them were stunted by lack of sunlight. Those that rose above, like cilantro, suddenly lacked a dense support of foliage around them when the nitrogen fixers were cut back. Therefore, I needed to tie them loosely to bamboo stakes in order to prevent them from falling over completely. Granted a reprieve from the highly competitive red clover and alfalfa, the other plants in these guilds were able to take full advantage of the extra sunlight and the soil was protected from the sun’s rays from the cuttings.

Largely left to its own devices after being opened up to the dogs when the fence was moved, I brought in a lot of very rough acidic mulch to bunker this the west berm extension down for what was clearly going to be a hot summer. As it turned out, 2012’s persistently high temperatures wound up being for the record books. I obtained these boughs from some landscaping I did for a neighbor and instead of breaking them into smaller pieces, I simply left them whole to seriously shade this berm extension. As it faces west, it is the hottest and driest part of the garden- conditions that blueberries aren’t known for tolerating. Yes, that is an entire young eastern juniper on the west side! At this point, with a wild cover crop in the main garden and this rough and ready approach to mulching, the garden was seriously breaking with convention.

The Berm: More than a Vantage Point

Despite being the vantage point for many of the panoramas of the garden, the southern facing berm, with its original topsoil and excellent aspect, hasn’t had much attention in this project review exception a rare occasion. Before closing the segment on May and chop and drop, here are some of the developments that had been underway.

I haven’t written much about the blueberries that I planted back in 2011. They’ve been largely left to fend for themselves- pretty much the habit we want to instill when it comes to perennials in the garden. If they survive with little to no attention, then we want more of them. In this case, the blueberries simply aren’t able to get enough water. Even though this photo has plenty of berries coming on, the fact that they are on mounds on top of a dry berm means that they will have to struggle to ripen many of these fruit. It will be best if they are moved to a better location.

The sheet mulched section of the berm needed to be resown after smothering some of the initial seedlings with white clover mulch. At the same time, we transplanted many perennials and vegetables. Wood chip that has been sitting in a pile in full sun for weeks on end will be rather dry, even to the point of being water phobic. To overcome this, we started filling buckets with pond water and packing wood chips into them. After letting the chips soak for at least half an hour, the much heavier, fully saturated wood was put down around vegetables and transplants.

Since I had finished digging the lower pond, I moved some water hyacinth and goldfish into it. As the surface area is quite large, I kept finding most of the plants languishing in the shade of the willow oak. I can’t have a sun loving plant doing nothing in the shade, so I crudely lashed a couple of bamboo canes together and used them as makeshift barrier to keep the hyacinth in full production. Finding a good source of native aquatic plants is still on our to do list: it seems very difficult to find anyone who has them as a priority. Perhaps this is because water features of this size and type are not quite yet popular. As I mentioned in the site analysis section, there are no natural lakes or ponds in this region of North Carolina, so finding even ubiquitous plants like cat tails (bulrush, Typhus) is difficult. Seeds may need to be purchased or bartered for online.

Lastly, we cut back a lot of chickweed in one of the most exposed hugel mounds and planted tomatoes and cucumbers along with herbs and cover crops as a mini vegetable patch.

June: Last month in North Carolina

My flight to Finland was June 18th, leaving me with a couple of weeks to tie up loose ends and say goodbye to my family. When it came to the garden, I was very happy with the way the summer was shaping up. The garden was responding very well to our implementation of mainframe design elements. The soil seed bank was expressing itself and we were able to manage many of the undesirable plants at the same time we systematically moved through the garden chopping and dropping.

The same lack of local sources for native aquatic plants is also affecting our ability to fill the marshy area between the two ponds with marginal species. Luckily, we already had horsetails growing on site and after a year in their new location, they were beginning to reproduce quite well. Horsetails are an ancient genus of plants that perform quite well in damp conditions, spreading like wildfire sometimes. Which just means (in a garden) that they should be harvested and used as mulch, to ferment into liquid fertilizer, or otherwise put to use as dynamic accumulators.

The sheer number of blooms around was a pollinator paradise. We still have a long way to go in providing them with other needs, such as food for their young which often comes from native species. Still, when compared with the lack of diversity before our garden began, things are definitely looking up!

A friend donated a lot of plants to us early in the summer when they did not find homes in the community gardens he runs. He also shared with us some divisions of plants from his own garden. Since the margins of our ponds were still glaringly empty, we jumped at the offer of some crowns of irises (Iris pseudacorus). While not native, they will still provide us with filtration and an early spring floral display. They crowns were further divided and planted into four or five locations in the ponds- at varying water lines- to maximize our chances of establishing a colony. When he returned for a visit in the summer of 2014, they had grown so tall that he believed they were cattails until I reminded him that they were, in fact, irises from his garden.

A little more practical diversification taking place was the spread of some native pollinator and tea plants we planted the year prior. Since many perennial herbaceous plants don’t reach maturity until their second year, it was a pleasant realization that they had survive the winter and were thriving. Wild bergamot is a very useful native plant: it is used to make tea while the fresh leaves and flowers are edible. We also had spread seed for its cousins Monarda didyma and Monarda citriodora elsewhere in the garden. These are plants we would love to divide and grow all over wherever enough sun is available for them.

In addition to the irises, we were also given about a dozen strawberry plants that had not found a home. Although midsummer is not the ideal planting time, with a little bit of attention in overcoming transplant shock, strawberries do extremely well on their own. We planted small patches of them throughout the garden in the hopes that they would take to at least one spot from which we would be able to make divisions in the coming years. At the time, yarrow, oregano, and white clover were our dominant desired species for that niche. Now, with the strawberries, we have brought into play a fruiting perennial as well. One other great thing about strawberries is that many of them carry on growing well into the cooler season, so we have yet another season extension of soil building. They also make a good ground cover around ornamentals like roses, seen above, planted for Mother’s Day.

Swales are truly multi-functional earthwork features because, in addition to rehydrating the landscape, they offer multiple niches. The swale berm is well watered, but also well drained. This is a perfect location for water demanding plants that do not like wet feet. The swale bottom, on the other hand, is the perfect place to plant water loving species. Here, we have Great blue lobelias in their second year. This particular swale was dug with a narrow shelf on the high side, putting into play a long bed for water loving plants. These Great blue lobelias are native so they support large numbers of insects, in addition to being beautiful. They are short lived perennials and produce very large quantities of seeds each year that can be spread along wet areas in the fall to encourage colonization.

I feel that the ponds were one of the best features we chose to implement early on. They offer year round interest and attract a wide variety of creatures to the garden.

Pulling up a chair under the shade of the pine trees and observing the garden while seated next to a pond is simply relaxing. The vantage point from under the pines offers unobscured views of the nearly the entire project.

The upper pond stays full much longer given its smaller size and its situation as the “first flow diversion” of runoff from the neighbor’s lawn. Both ponds are situated such that they are well shaded in the afternoon by the existing trees. This helps keep them from losing too much water to evaporation as well as keeping the temperatures from fluctuating too much. It may be that they are buffering the surrounding air temperatures as well during the summer. Since they are not too deep or large, preventing the temperature from climbing too high is conducive to healthy fish, frogs, and habitat. They still get enough sun in the morning to fuel the growth of the water hyacinth, which as mentioned before, we keep at about 1/3 to 1/2 the surface area by harvesting it for mulch.

Observable near the pond in Photograph 3-79 are “towers” of lettuce that sprang up around the garden as the winter-cropped lettuce began to flower. While we continue to bring in new lettuce seeds to increase the genetic diversity, we allow nearly all of our vegetables to breed and self-sow to establish local varieties.

After two years of gardening with ponds integrated into a passive water harvesting system, I’ve come to appreciate their benefits to the point of not being able to imagine a garden without a pond of some kind. They simply make sense, even if you don’t have much space.

Speaking of water features, I was inspired to dig Zai bowls (mulched pits) just before leaving the country. I wish I had wanted to dig them earlier in the year! I dug small pits along the eastern fence line and filled them with wood chip mulch. I packed the chip in so that as you walked along the fence to cut back growth from entering the neighbor’s yard you wouldn’t sink in and twist an ankle. The bowls were attached to one another by the Type 1 Error I had made back in the beginning of 2011 by digging the overflow ditch between the upper and lower swale. In this way, if one bowl filled, then the water would be directed into the next. Turning an old problem into a solution! Eventually, these bowls will reach all the way down the length of the fence line to help absorb the shock of runoff that comes from the neighbor’s lawn. I am also hoping that the amount of biological activity in these Zai bowls will help buffer any chemicals that our neighbor uses on her lawn. Perhaps they will be intercepted by the carbon filter and have time to degrade. Diverse water harvesting features, scattered throughout the garden, help add lumpy texture and create wet/dry places that otherwise would remain uniform.

False Indigo (Amorphous fruticosa) seedlings looked strong enough to be transplanted into the garden much earlier than usual: typically one would wait until they have grown for a full summer. But because I had more than one sharing a container and we can afford to pay attention to them, I transplanted them into the newly sheet mulched area. False Indigo bushes are highly attractive nitrogen fixing natives that do well with coppicing, so they are perfect for woody chop and drop. I am recommending stacking many more into the system at least for the next few years.

In the old four sister’s guild, the wood chip mulch apparently didn’t stop these brassica seedlings from germinating in the height of summer. Dispersed by birds in the spring, this is an example of naturalizing species in the garden. Over the course of a few years, local landraces that bear little resemblance to their parents will emerge since we plant only open pollinated species (except those Sun gold Cherry tomatoes!).

Like the other native perennials we planted the first year, these Echinacea plants began to reach maturity by the middle of the summer. Displaying exquisitely beautiful flowers, Echinacea are wonderful as they require little water or care but still provide tea that is purported to help our immune system. Interestingly, they are related to sunflowers by sharing the same biological tribe: which helps explain their allure for pollinators of all stripes.

Emigrating to Europe & 2012 Conclusions

Leaving- once again- in the middle of the growing season, but this time for good, was difficult knowing that my situation in Finland would leave little room at all for the level of interaction with nature I had grown accustomed to. I was happy that I had been able to spend so much of my life interacting on a daily basis with developing ecosystem. It was very rewarding to see how the thorough application of mainframe permaculture design could swing a degraded landscape towards regeneration in such a short period of time. The decision to focus on cover cropping and building soil organic matter before the canopy closed was a good one.

The months of 2012 flew by because we simply needed to observe, adjust, and cut plants for mulch. They didn’t require any additional watering, besides transplants, and the little bit we extended the garden was easily manageable. The amount of work required to keep the garden alive should have been quite low, though of course new plant growth in July and August can quickly overwhelm even the most dense cover crop if troublesome plants are not identified early.

Both the alfalfa and red clover responded very well to the chop and drop regime, as did the year old comfrey plants. A few more years of concentrating heavily on increasing the soil organic matter should prove quite fruitful. By 2013, the thick lines of comfrey dominating the swale mounds would be producing plenty of mulch for any new plantings.

The sheer amount of life that sprang up after a mild winter was bewildering. At times it was difficult to remember that we had set the stage and brought in many of the actors, as the cover crops dug deep and new arrivals poured in day after day. Although the pace will eventually slacken, it is reinforcing to see that our experience matches the models for ecosystem change.